CPU limits are probably the most misunderstood concept in Kubernetes CPU resources allocation and management.

A lot of engineers advise the use of CPU limits on every container as Kubernetes best practice. Unfortunately, as we will prove below, they are wrong: CPU limits should rarely be used, if used at all!

But why? What are the reasons that even senior DevOps engineers with vast experience in the field advise the use of CPU limits?

By discussing this subject with DevOps engineers, I understood that they use CPU limits for one or more of the following reasons:

“To ensure cluster stability.”

They are afraid that without CPU limits, crucial Kubernetes components will be starved of CPU resources and eventually the cluster will become unreliable and unstable. This is a myth! K8s components will always get their fair share of CPU resources, no matter how much load we put on the cluster. In fact, K8s configures CPU shares in such a way that it is impossible for its crucial components to be starved of CPU.

“To ensure fair distribution of CPU resources among different hosted services.”

Engineers believe that without set CPU limits, a service may monopolize the available CPU resources and eventually impair the performance of other services running on the cluster.

This is also a myth. CPU requests define the relative CPU weights on which CPU resources will be allocated. CPU requests, not CPU limits.

During my interaction with DevOps engineers, I finally realized that there is another reason, never openly admitted, but there nevertheless:

“Rather be safe than sorry!”

When engineers deal with an “important matter" such as a production k8s cluster, they’d rather err on the safe side, and assume CPU limits will isolate potential bad actors from other services running on the cluster.

It seems logical, but the real benefits from such a strategy are so minimal—and its consequences so dramatic—that there is really no value in this strategy.

Why are CPU limits bad?

CPU limits set a cap, or ceiling, on the CPU resources a container can use—for example, you might limit a container to use up to 1 CPU core.

And here come the problems:

“It uses just half a core, so the limits are fine.”

Wrong! Depending on the type of load, the application may be severely throttled. Why? Most modern applications are multi-threaded. A web server spawns several workers to service incoming requests, with these workers running in parallel on multi-core hardware. If 10 workers want to use 100ms each, they will exhaust the 1 core limit in just 100ms, so their average CPU utilization over a period of 10 or 15 seconds will not even be close to 50%.

To hide the problem even deeper, engineers frequently use the average CPU utilization of multiple containers to make such judgements.

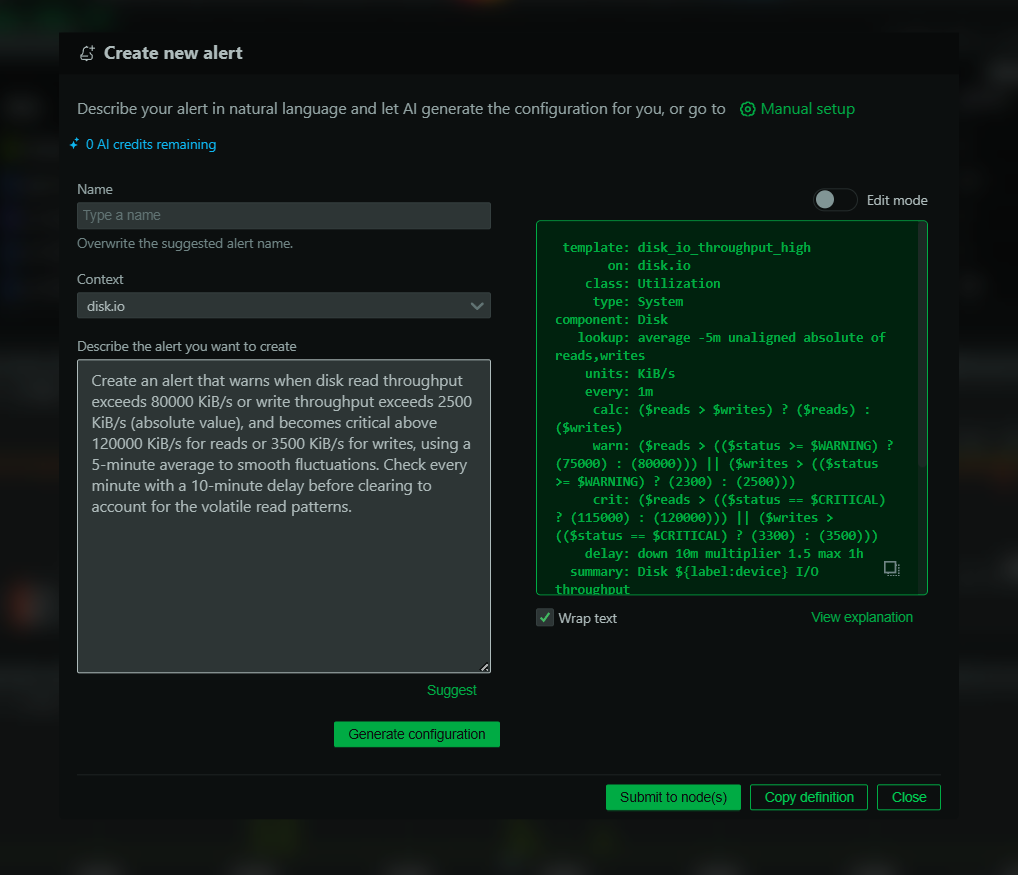

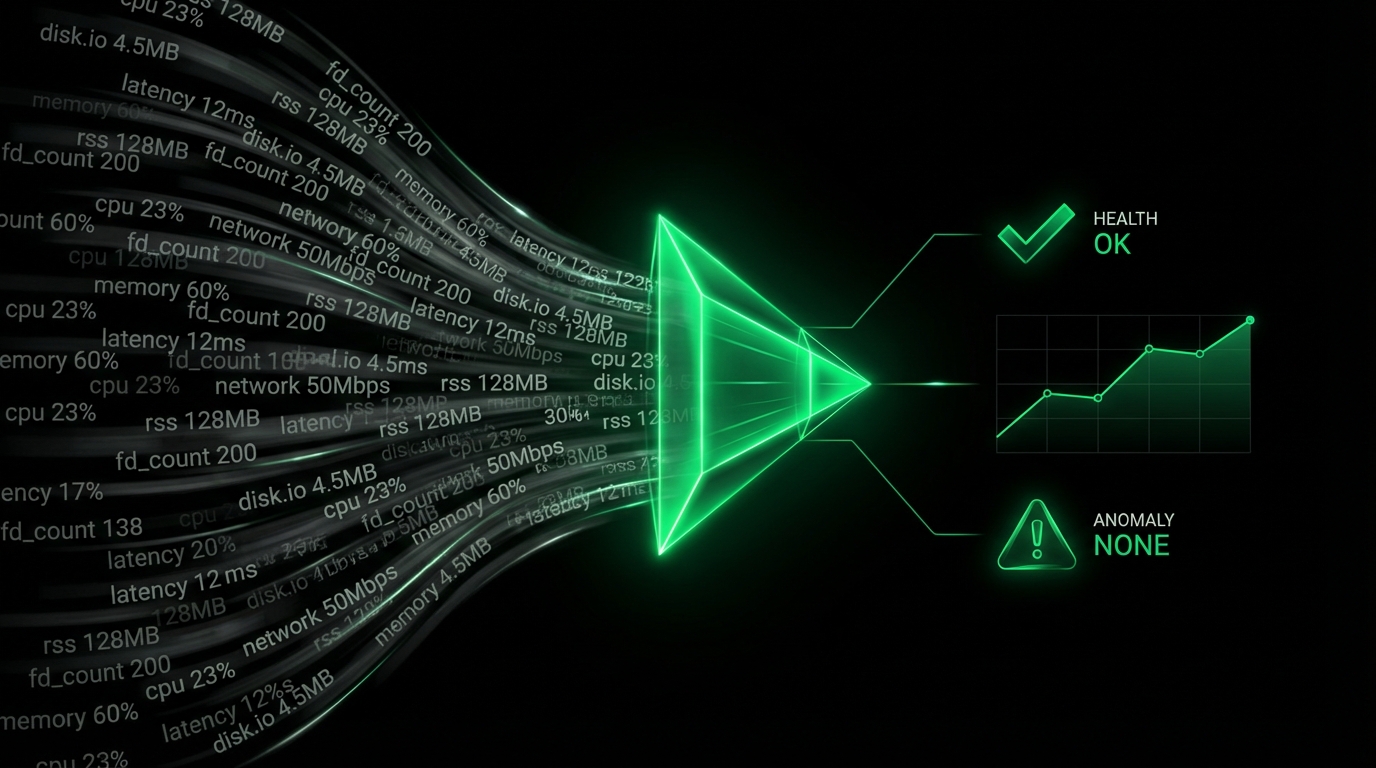

Using high fidelity monitoring like Netdata’s, with a 1-second interval, we observed that a web server container can be throttled by up to 50% while its average 1-second CPU utilization is below 80%. On busy web server containers, throttling kicks in at about 60% of average 1-second CPU utilization.

“The hunt for the slow response.”

This is probably the biggest time-waster ever. All kinds of wrong conclusions play a role: “The DB couldn’t do it," “This request handling is badly written," “The slow request had something special to do," and many more. All wrong.

We have been here ourselves, and what did we discover, after spending weeks hunting slow responses? By simply removing CPU limits from containers, we managed to reduce response times . . . by a factor of 7.

Severely underutilized clusters

This is the biggest waste of money yet: CPU requests cannot be overbooked. If you have 24 cores, you can distribute 24 cores to containers. Period. But when people set limits, they usually set them equal to the requests or at most double. It is very rare to see a limit 10 times bigger than the request. This has the effect that the only way for the cluster to get more capacity is to scale out, to add another node to the cluster. The result of this is that the cluster gets a lot of nodes with 5%, 10%, or 15% of total CPU utilization.

Modern multi-core hardware and Linux kernels can perfectly utilize all the available resources. Of course, we shouldn’t be running our clusters at 100%: response latency will suffer at that level. But it is reasonable to expect at least 50% of total CPU utilization of all nodes in the cluster before a new node is required. Anything below the 50% threshold and you’re probably wasting your money.

The only way to know for sure that your containers are not throttled is to use a tool like Netdata that collects and visualizes CPU throttling metrics directly from CGROUPS. There is really no other way to safely conclude that your services are not being throttled when using CPU limits.

We did our own lab test to see how throttling works. Check it out in the video starting at 11:03!

Cluster stability

K8s nodes ensure their crucial services will always get the CPU resources they need. This is done with CGROUPS CPU shares, like this:

At the cpu controller of CGROUPS, we can see that there are 3 top level CGROUPS:

- system.slice, with a CPU Share of 1024 (100% of a single core)

- user.slice, with a CPU Share of 1024 (100% of a single core)

- kubepods, with a CPU Share equal to the number of cores in the node, times about 1000, so for a 4-core node this will be about 4000

At 24:06 in the video, we show in detail how K8s manages to remain stable under extreme CPU loads.

Fair distribution of CPU resources on hosted services

All our containers run inside the kubepods top level CGROUP hierarchy. As we show in the video, all our containers are grouped in 3 categories:

- Guaranteed containers — with CPU Shares defined as whatever we set as requests and limits (requests and limits have to be equal for a container to be guaranteed)

- Burstable containers — with CPU Shares defined as whatever we set as requests.

- Best effort containers — all of them together allocated 2 CPU Shares (0.002% of a single core).

In the video, we show that k8s actually does an amazing job of respecting the relative weights of containers. By just setting CPU requests, each container gets its fair share of CPU resources.

Final words

- CPU limits are really confusing: they may influence your applications’ response latency significantly and it's hard to predict when they might kick in. Unless you have a very good reason to use them, don’t.

- CPU requests alone are perfectly adequate for defining CPU weights among containers, and the Linux kernel does an amazing job of allocating them to containers.

- The K8s cluster stability is not threatened by the absence of CPU limits. The crucial K8s services will still run as they should.

- CPU limits will not protect against increased latency. Under extreme loads, latency will increase. The only way to avoid this is to configure the K8s cluster to add more nodes, providing more compute capacity to the cluster.

Still doubtful about removing CPU limits from your Kubernetes clusters? I suggest you increase them significantly and install Netdata to monitor them to ensure important applications are not being throttled. (And hopefully our solutions and demonstrations will help you dramatically reduce the cost of monitoring and maintaining your infrastructure.)

Look out for more news about our K8s monitoring capability—in the meantime, find out more on our website and our knowledge docs. Thoughts, questions or suggestions? Share them on our Discord server or community forum!

Note from May 10, 2022: This article is an updated version of an article published on May 2, 2022.